Cavemen and the Internet

The problem with you––and by you, I mean me––is that our brains are built on a 40,000 year old platform. Let's not forget, evolution is a slow process. We haven't had any significant brain upgrade since our ancient ancestors started sprucing up their cave walls with paintings of local fauna.

We may marvel at our technological advancements, but despite our ability to hurl metal objects and ideas through space, we are basically cave dwellers dressed in modern garb. In fact, the technology we all enjoy (most of the time) was the work of only a few individuals. Who among us, if teleported back 40,000 years could reproduce an iPhone, a cylinder lock, or even a porcelain toilet? You get the idea.

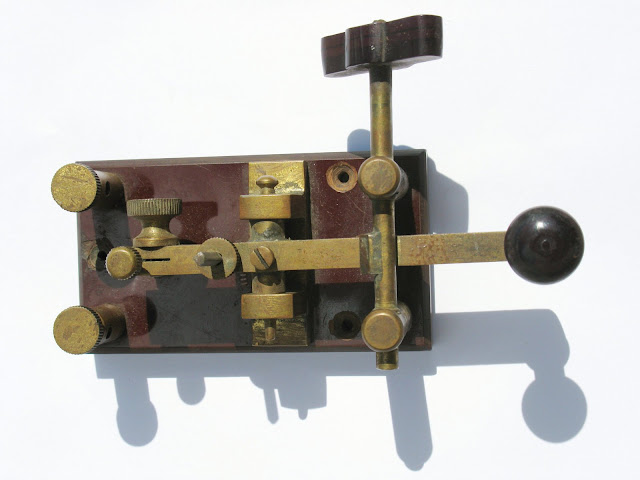

Imagine a stunning technological advancement, one that almost seems like magic. It's a method of communication that allows us to share ideas like never before. Suddenly, news can cross an ocean before you cross the street. You can read about the results of a battle in Europe as the wounded are still en route to the hospital. Country by country is hooked up, and soon we are nodes in a dense, complicated network––a "web", if you will––covering the world. Suddenly, it is possible to have lengthy conversations with someone, play games, flirt, and even fall in love, all without ever meeting face to face. The world is smaller and larger than ever before.

There's a dark side, too. This new world is filled with people trying to work the system for their own advantages. And it brings into being types of crimes that couldn't have existed twenty years earlier. People complain that they're being flooded with information––so much that it's impossible to tell the signal from the noise. Attention spans are surely shrinking. The newspapers fear they are about to become obsolete.

You're thinking of the telegraph, right?

In his book The Victorian Internet, Tom Standage draws a number of startling parallels between the advent of modems and the advent of Morse code. It may all seem impossibly quaint now, but the telegraph marked a turning point in human history: for the first time ever, ideas could travel faster than people. Actually, that's not quite true; carrier pigeons had been used for centuries. The Reuters news service was originally one guy, Paul Julius von Reuter, tying stock information to birds' legs.

Still, pigeons had a flight range, a shelf life. When the option arose, Reuter switched to telegraph cables without a second thought. Birds weren't reliable enough, and newspapers could no longer get away with printing the latest from Paris eight weeks ago. It was a new era, and in a way, the beginning of the 24-hour news cycle.

There were hackers, after a fashion, too: crafty men and women who sent their messages in abbreviations and code so as to cut down on their telegram fees. This was not allowed in the U.S., so there was an endless cat-and-mouse between the telegraph companies and the cipher-makers. The result was a huge increase in sending "nonsense words" like "GNAPHALIO" ("Please send a supply of light clothing.") It got so bad, telegraph companies attempted to make a list of all approved words in eight languages and to ban everything else. This didn't go so well; turns out languages have a lot of words.

And while it's true that most folks weren't spending hours in front of their own private line, refreshing their telegraph over and over, there was one class that did spend all day "chatting"; telegraph operators. 60 hour weeks were common, and during downtime, the operators often sent messages to each other. Sometimes they played checkers, using a system of numbered squares. Sometimes they told stories, most of which were apparently too ribald to record. And yes, they did occasionally fall in love. Male and female operators were generally kept in separate rooms for propriety's sake, but given their line of work this didn't exactly isolate them from each other.

Basically, the only thing the Victorian internet lacked was lolcats. And had the Victorians found a way to share their own humorous cat photos via dots and dashes, you know they would've jumped on that in a heart beat.

So although technologies come and go, and some may feel eerily familar, that one constant, us, remain unchanged. As it has been for the last 40,000 years our brains can be counted on to do one thing, behave the same old way. Which is to say, same caveman, different day.

Check out Robb’s new book and more

content at www.bestmindframe.com.

Comments

Post a Comment